Was this a

paraphrase of a providential directive by a specially chosen servant, or the direct

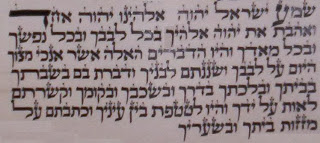

words of God? Moses spoke most of the original words of the song “Hear, O

Israel” (see all of the words of this command in Hebrew here)

to a nation,

followed centuries later by the Son of God who was also speaking to a nation. Did

the words sink in? One can hear them, but doing them… How would you or I behave

as we prepared to accept an inheritance larger than anything we could ever imagine,

with the only stipulation being unswerving loyalty to the one with the key to

the bank? Hmmm. That might be a tough choice, if you think about it. Or is it?

Moses was

telling the people he’d led to the edge of their new home some very important

words, so important that another of God’s representatives – His own son – would

discuss them again some fourteen centuries later. Moses was a very old man by the time he said ‘Hear,

O Israel’ outside of the perimeter of Canaan (Deuteronomy 6:4-5). He’d been

through so much to bring the people out of bondage and entreat them to

obedience. It must have also been a somewhat bitter irony for this 120-year old

to speak these words, as he himself would not be allowed to enter the land

because of a mistake he’d made in regard to obedience (Numbers 20:9-12; Num.

27:12-14). Were they in fact his own interpretation of what God told him to

say, or God’s own words that he was merely repeating? Moses indicates that

these are in fact God’s words (Deut. 6:1-2), and he would have undoubtedly been

quite reluctant to alter them significantly. The Lawgiver’s words are recalled by Jesus

over 1,400 years later as he taught some devout lawyers – the Pharisees. He

adds something to what Moses had said, something about how to love a neighbor

(Matthew 22:37-38; Mark 12:29-30; Luke 10:27; Leviticus 19:18). Why’d He do

that? Could it be that the omniscient God – Jesus – knew honoring God and treating

fellow humans charitably were not always congruous? What happens when some of

us are very good at following His rules, and likewise good at catching others

who’re not so good? Sound at all like the 1st Century, perhaps? Or

even the 21st Century?

The

challenge in hearing what He directs is that it doesn’t stop there. I must do

it. And, there’s that word all. It’s

so small, but it does make this command rather comprehensive. All heart, all

soul, all strength, all mind. All of me

needs to engage in this imperative. It’s called ‘the Shema’ – Hear. First

spoken by Moses, it was a lesson he must have wondered ‘Will this really sink

in? Will they remember that I tried and failed at this?” Love. All. They’re

small words. Try ‘em out.

There is no source for the song story, but for background on

the song, see the New International

Version Study Bible, general editor Kenneth Barker, 1985, copyright The

Zondervan Corporation, for notes on Deuteronomy chapter 6, verses 1-5, and other

scriptures therein.